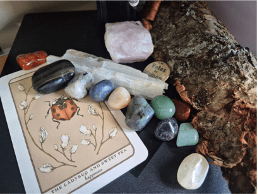

Figure 1 and Figure 2. “The act of choosing an area within my home to place and curate some selected objects gave both objects and the location a new depth of meaning for me. Initially, the objects were located in different areas of my home, so when they were placed together, they became related and connected in ways I wouldn’t have noticed previously. I felt a wonderful sense of having control over this small area of my home, where I often feel control is lacking due to living in a busy household and working long hours. This resulted in an inner feeling of peace and pride because I’d created something beautiful with little effort using objects that were mine” (Research participant, personal communication, August 25 2025).

Ecologies of Care: Reflections and Impact

An ecology of care is a situated practice within architecture, which designs spaces for encounters, reflections and social relations. Space activates interactions between people “paying attention to one another [and] recognising kin in a multitude of users’ situations” with both people, materiality and the built environment(Architectural Humanities Research Association, 2023).

Art psychotherapy learners were invited to develop ecology of care home studio displays which resonated with their classroom experiences. Chamat Garcés (2025) highlights the pluriversal nature of higher education existing beyond the university classroom to the home environment. Online learning in higher education produces correspondences to home environments of learning and a kinship between learners who share their home backdrops on a computer screen. The pluralistic nature of learning ecologies (as an assemblage and entanglement) requires “a more expansive [and] relational…reimagining of higher education learning spaces in ways that embrace the diversity of being, knowing and relating to the world” (Chamat Garcés, 2025, p. 69). A learning environment should produce a dynamic learning web networked by spatial learning configurations which “can accommodate the non-linear and emergent nature of knowledge and skills development (Chamat Garcés, 2025, p. 72). The democratisation of the educational space facilitates co-habitation and multiple ways of situating learning (Chamat Garcés, 2025), which involves the domestication of classrooms in order to accommodate learners feeling more at home on campus.

Danvers and Wells refer to this as the homeification of learning, the blurred boundaries between learning within both public and personal locations (Danvers and Wells, 2024). “Learning involves a complexity of micro practices, that learners are entangled within, and shaped by…the physical and material form of the university is not a blank space within which learning happens but the interplay between space and people” (Danvers and Wells, 2024, p. 35).

The artefacts of a learner’s home environment, “a curated den” (Danvers and Wells, 2024, p. 38), can enter into the public homeplace of the university through emotional connections evoking place attachment. Place identity and attachment are “crucial for creating enriching and supportive university environments that foster students’ personal growth, well-being and academic success” (Khaidzir and Ahmad Kamal, 2023, p. 1021). Memorable moments within a learner’s lived experiences of university life provide a sense of purpose, belonging and bonding. Higher eduction teaching is about presence and a pedagogy of mattering that challenges a university business model grounded in neoliberalism. “Pedagogies of mattering…enable us…to tune into the objects, bodies and spaces that constitute the material mattering of learning as an in situ practice of relationally” (Gravett et al., 2021, p. 393). Higher education can be considered an event with materials, people and place, a situation that is not predetermined, but enacted as a making of becoming (Abegglen et al., 2025).

Figure 3. Simple Moments. “The materials and items in my table display carry memories of meaningful moments—glimmers that evoke a sense of wellbeing. Simply seeing them can awaken those memories and bring about a feeling of calm and grounding” (Research participant, personal communication, July 15 2025).

Student Responses to Ecologies of Care in the Art Psychotherapy Classroom (July, 2025)

Identified Themes: Nesting, Relaxing, Gentle, Welcoming, Inviting, Soothing, Sensory, Nostalgic

“I found the ecologies of care to be a really gentle, warm and inviting practice. You showed some thoughtful yet subtle ways of providing softness, using natural materials to create an atmosphere and tune into the senses.”

“Thought inducing moments creating personalscapes in various settings. Nesting, both at home, at university and at work. It was welcoming.“

“I really enjoyed participating today. It was relaxing with no feeling of pressure. The colours and smells of flowers brought calm to my urgent nervous system.”

“I appreciated all the thought and care you have put into ecologies of care right back to the beginning of our course. It has been a sensory feast and provides a feeling of being cared for. I am eager to include more of this practice in my art therapy practice. It is very gentle and soothing. I am also fascinated by the natural elements and the therapeutic effect of appreciating the artistic colours and design.”

“This was a beautiful tactile experience. A feeling of growth both during the course and the next steps.”

“Very enjoyable and insightful. Each session grounded and brought my body to engage with my senses. Smell has been a huge factor with the use of natural materials and evoked childhood memories.”

“Loved the togetherness of today’s project and the intentions. Very calming and grounding, and it felt nostalgic to me.”

“So simple, beautiful and engaging. I really enjoyed this.”

Figure 4 and Figure 5. The Space Between Things. “This home décor arrangement reminds me that care can be both felt and arranged, intuitively composed, yet deeply significant. It reflects a personal ecology of care, a quiet system of interconnected elements that nourish, support, and transmit care to me. The jade plant anchors the scene, symbolising rootedness and regulation. Around it, natural forms, handmade objects, and found materials form a small altar of presence. More than decoration, this is an invitation to attune, to slow down, notice, and connect with nature, memory, and self. In my art therapy practice, I’m increasingly aware of how such subtle ecologies shape the therapeutic space. The placement of materials, the presence of organic forms, and the quiet symbolism of everyday objects foster safety, containment, and relational depth. These are not aesthetic choices alone, they are intentional acts of care. Bringing this ecology into my work honours the body, the image, and the environment as co-regulators, each holding space for what may not yet be spoken” (Research participant, personal communication, July 22 2025).

Figure 6. “An [ecology of care] display sits just beside my laptop and screen. It’s a small, intentionally placed arrangement with stones, that brings a sense of calm and balance to a space that can easily become busy or intense. It acts as a visual reminder to pause, breathe, and take a moment to reflect, especially during full days or when shifting between tasks. It offers a quiet invitation to slow down and reconnect with myself, even if just for a moment” (Research participant, personal communication, July 25 2025).

Figure 7. An ecology of care home display by a research participant which includes curios, gifts, and mementos which support both study and career motivations (Research participant, personal communication, September 1 2025).

Figure 8. “This is my coffee table in my living room, that I regularly change and redecorate with new objects that are meaningful to me. I resonate with Lisa Hinz’s Life Enrichment Model of changing artwork in the home regularly in expressive ways as an act of mindfulness. I also live on a houseboat/barge, so every space is important as our home is so small. Art therapists often create an atmosphere (a therapeutic space) in a variety of different and changing settings. I want to adopt this idea in my own practice!” (Research participant, personal communication, July 15 2025).

An Ecology of Care and the Life Enrichment Model

Dr. Lisa Hinz is a Visiting Professor for the MSc Art Psychotherapy course at Ulster University. She has written a book titled Beyond Self-Care for Helping Professions: The Expressive Therapies Continuum and Life Enrichment Model. The book highlights self care strategies for health professionals and can also be referenced in relation to the ecology of care model. MSc Art Psychotherapy trainees have been inspired by her approach for professional self care, which incorporates an intentional approach to avoiding professional burnout, vicarious traumatisation and compassion fatigue. Everyday creativity, reflected in home based ecology of care studios offers art psychotherapy trainees a strategy for pursuing life enrichment through creativity, savouring (short interludes of making as micro-care practices) and honouring what is already in place within one’s life—the “objects, events and experiences that increase vitality and joy in life” (Hinz, 2019, p. 18). A number of MSc Art Psychotherapy graduates are now considering the potential of offering the ecology of care model within their professional practice, as a way to value the material cultures of art therapy service users and offer a psychological foundation for creative experimentation.

Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11. “The scenery of a dissertation presentation produced by an art psychotherapy trainee, incorporating her grandmother’s garden table, flower seeds, and lettuce transplanting. The student shared the significance of making herself feel at home by bringing materials from her home environment into her dissertation presentation on campus. This created a staging of her professional portfolio, which had also been incorporated into her practicum practice and dissertation research. She installed a potting shed as an example of a ecology of care studio, encouraging colleagues to make themselves at home within her own life story of growing up on a farm in a rural environment” (Whitaker, 2025).

References

Abegglen, S., Menon, A., Costin, K., Neuhaus, F. (2025) Academic wintering: Embracing warmth, inclusion and renewal in higher education. Available from: https://blog.westminster.ac.uk/psj/keynotes-and-talks/academic-wintering-embracing-warmth-inclusion-and-renewal-in-higher-education/ [Accessed 7 September 2025].

Architectural Humanities Research Association (2023) Situated ecologies of care. Available from: https://ahra2023.org [Accessed 6 September 2023].

Chamat Garcés, K. (2025) Re-weaving learning ecologies: A pluriversal framework for higher education learning spaces. Higher Education Research & Development, 44 (1), 68–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2024.2429439

Danvers, E. and Wells, A. (2024) The homeification of learning in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 44 (1), 33–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2024.2429441

Gravett, K., Taylor, C. A., and Fairchild, N. (2021) Pedagogies of mattering: re-conceptualising relational pedagogies in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 29 (2), 388–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.1989580

Hinz, L. (2019) Beyond Self-Care for Helping Professions: The Expressive Therapies Continuum and Life Enrichment Model. New York: Routledge.

Khaidzir, M.F.S. and Ahmad Kamal, M.A. (2023) Sense of Place: Place identity, place attachment and place dependence among university students. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 13 (10), 1020-10233.

Whitaker, P. (2025) An Ecology of Care in Higher Education: The Studio Classroom, PHE 720, Action Research Project 2024-2025. Ulster University. Unpublished Project Report.

Featured Image Photo Credit: Jacqueline Gallagher’s assembly of classroom objects composing a depiction of home within the art psychotherapy learning environment for a studio practice called Found Objects, Assembling Narratives (MSc Art Psychotherapy Blog, 2023)